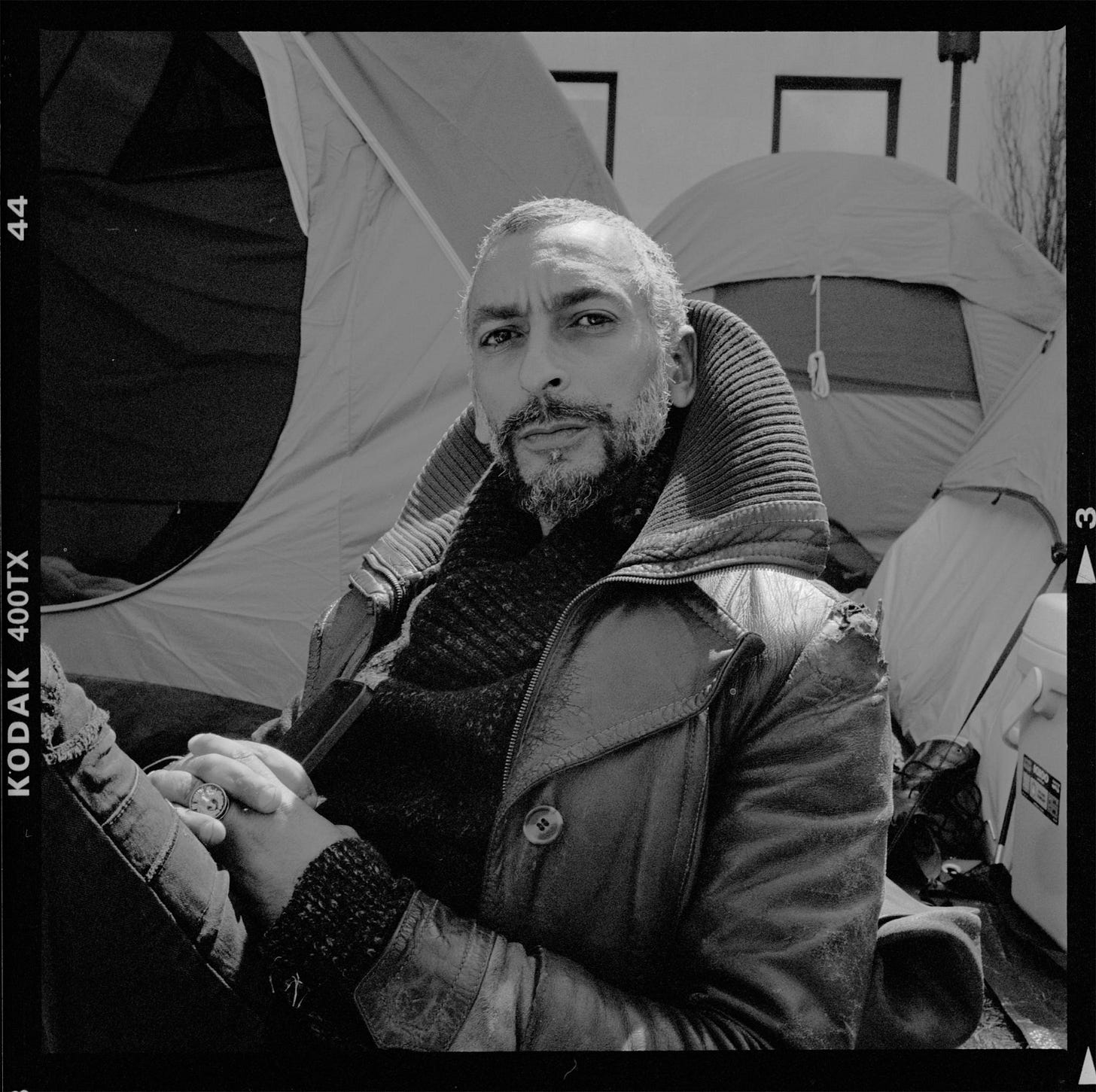

Beyond the Encampments: The Transcendent, Provocative Wisdom of Dr. Mohamed Abdou

Amanda Gelender interviews Dr. Mohamed Abdou, one of three Columbia University professors defamed at a Congressional hearing in April for their support of the liberation of Palestine.

For the past several weeks, I’ve had the good fortune to spend time with — and learn from — Dr. Mohamed Abdou, interdisciplinary scholar-organizer and author of the book Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances (2022).

Mohamed is also known as one of three Columbia University professors (Abdou, Joseph Massad and Katherine Franke) defamed at a Congressional hearing last April for their support of the liberation of Palestine.

After slandering them on a global stage, Columbia President Minouche Shafik declared about Dr. Abdou specifically: “He will never work at Columbia again.” The public ouster occurred on the same day that Columbia students established a “liberated zone” encampment, which expanded to “Hind’s Hall”, and ignited a global wave of student encampment protests.

After the Congressional hearing, Mohamed’s life changed dramatically. President Shafik torpedoed active efforts by students and faculty to hire Mohamed on a more permanent basis, beyond being an Arcapita Visiting Assistant Professor. Additionally, he was — and still is — harassed, stalked, doxxed, and blacklisted from academia. He has endured online and in-person attacks daily and has become a target in conservative media. Mohamed has been hunted by the Proud Boys, and spat on by detractors. Because he was a non-tenured professor with his work visa tied to his faculty position at Columbia, in addition to being “unhirable” in American academia, Mohamed was forced to leave the country.

The targeted harassment campaign against Mohamed goes beyond the standard racism and Islamophobia that fuels Zionist persecution campaigns against academics and others across fields who advocate for Palestine. Mohamed’s scholarly work itself has also come under fire, with opponents particularly threatened by how he links the struggle in Palestine to the struggle for Land Back on Turtle Island.

He has enraged individuals on a wide political spectrum for his refusal to dismiss Islam, religion, and faith in liberation movements, alienating the right along with progressives and the western secular left. Mohamed emphasizes that the land is not an object, but a spiritual subject. He notes that development of religion in the global north is radically different than in the global south, citing Kwame Ture when he says, “You can't be revolutionary without being religious.”

Talking with Mohamed is to engage at once an intellectual, a young movement elder, and a spiritual teacher. He is a North African-Egyptian Muslim anarchist, scholar-activist, and diasporic settler of color.

Mohamed offers vast expertise across fields, including the combination of Black, Indigenous, critical race, and Islamic studies as well as gender, sexuality, abolition, and decolonization. He weaves encyclopedic wisdom through a myriad of symbiotic reference points.

Central to his scholarship is the race-religion entanglement of 1492 which sets the context for decolonial struggles globally, including in Palestine. Mohamed’s academic work is inextricable from his decades of movement experience, including Tahrir Square during the 2011 “Arab Spring” uprising, post-anti-Globalization Seattle 1999 organizing with Tyendinaga Mohawks, and his time living with the Zapatistas in Chiapas.

He is a learned movement organizer whose scholarship is in no way hypothetical: It is birthed and sharpened from time in the trenches, from his faith, from the land, and from the revolutionaries upon whose shoulders we all stand.

My conversations with Mohamed move dizzyingly from topic to topic; we are stones skipping through the waters of history, philosophy, religion, liberation, queerness, and decoloniality with velocity. As I listen and we discuss his ideas, I find myself drawn to the simplicity of his pursuit:

What is the story we must tell about our intersecting liberation struggles? And what frameworks can we draw on from the past in order to build a just future?

Gelender: I know that many of your students at Columbia were organizers at the encampment who were arrested by the NYPD, and you were the first — and one of the only — Columbia professors who taught your class outside in the ‘Liberated Zone’. What was your impression of the student encampments and what do you see as your role moving forward?

Abdou: I’ve written about biodiverse strategies of resistance and lessons learned from the Zapatistas in terms of alternative ways of being. The Columbia encampment started to establish the creation of a new formulation of society. They embodied a different way of being, celebrating and praying together, breaking bread together, living together, connecting with the land. So the student Palestine encampments became dangerous because it provided an alternative to society. They threatened not just Columbia, but the settler-state.

These students, they get it. They are organized. The students lead and we support them. I’m in awe of our youth and I’m humbled by them. They are our spine and the whip of a tongue that we speak through and with insofar as our values, justice, and our compass with regards to the liberation of Falasteen and Turtle Island.

The youth dream wildly before we tame and domesticate the possibilities and impossibilities of life. This is academia exposing itself as a wing — an extension — of the settler state in which the settler state is now directly commanding what is taught.

Academia is a site of resistance, not liberation. There wasn’t anyone who told the youth at Columbia to move from the South Lawn to the East Lawn the day the police were called in and my students were arrested. It was spontaneous in which people started to climb the fence. No decision makers, no leaders, and everyone joined. Very spontaneous. Very anarchistic. Very anti-authoritarian. And can we live that way, with a degree of permanence?

I asked my students: Why aren’t you establishing a community garden? You’re here to stay, right? This is a liberated zone. Land Back. Black Liberation. Against gentrification, etc. You need to develop the means for your own sovereignty.

[Moving forward] the most honorable thing I could think to do is to be a knowledge keeper and knowledge producer. The task of a scholar is not to indoctrinate, it’s to open the purview of the world for students to make their own decisions and for them to understand how we can interrelate to one another as a species. What is the role of non-human life in terms of inspiring us? What can mother earth teach us as we walk along? My students, I walk with them. They teach me every single moment of every day and I miss them so much since I've gotten taken down.

I’m trying to help birth a new world, one that I lived in the encampments, a new world I lived in with the Zapatistas, and in my 18 days at Tahrir Square. It’s a world without nation states, without borders, without capitalism. A new world in which alternatives premised on shared political, ethical, and spiritual commitments are embodied in our day-to-day lives. A world that is based on a politics of responsibility. A world that’s based on organization and not mobilization. A world in which identitarian politics are irrelevant. I’m trying to build an Ummah, for lack of a better phrasing or concept or word.

Gelender: For those of us who are not Muslim, and maybe even for some of us who are, can you please expand on how you define the Ummah?

Abdou: As Muslims, we are brought up on the idea of the Ummah, the global community. And there is discussion amongst Muslims as to who that includes. The Ummah is defined as a community of “believers” – whether they are Jewish, Zoroastrians, Christians…whatever they be. And there are many paths to the believer, call it Creator, Yahweh, Buddha, Allah . . . “The believers” is the category that prevails in the Quran, in fact the word “Muslim” only appears 5 or 6 times. The emphasis is on the word believer. And the believer is one who does not corrupt the earth, the one that minds the rights of the poor, the elderly, the gender dissidents, children, and so forth.

There’s an acknowledgment in Islam that 200,000-300,000 prophets were sent to different tribes and nations so that you may — so that we may — get to know one another (Quran 49:13). And the best among you anchors in piety – what is piety? Social justice.

[The Ummah] means building a new society together based on shared principles that are not identitarian. Because I see you as a believer, a believer that fits within my Ummah more appropriately than some Muslims who are misogynist, queerphobic, or even Zionist in this day and age. So are those Muslims simply a part of my Ummah just because of labels or names that they take up? Or is it a set of ethical, spiritual, and political commitments that informs their sense of identity? So this is the coming world or Ummah that I want to aspire to, beyond identitarian politics.

Gelender: You are not only an academic; you’re a seasoned movement organizer, which is clearly at the forefront of your work. What advice do you think is most pertinent for people building liberatory social movements beyond the encampments?

Abdou: Revolution is about practical questions. What are you going to do when someone gets hungry? What are you gonna do when someone gets sick? When something happens, what is the recourse? What’s the alternative life going to look like?

This involves building sustainable worlds of ‘below’ to counter the worlds of ‘above.’ How do you do that without land? And in this case, without Indigenous people who have sovereignty and a mutually constitutive relationship with the land?

[People who] are constantly talking about destroying and dismantling but never talking about building or creating . . . they’re not revolutionary. They don't understand the first thing, actually, about revolution. This is Kwame Ture. Revolution is about creating and it’s creating a total culture of life. This is what Walter Rodney teaches.

You have to think logistically — you’re not gonna sit in tents in the middle of winter, so how do you prolong it? How do you establish alternative schools, alternative everythings? In the gentrified neighborhoods? How do you protect it so that police can’t walk into the new neighborhoods? How do you establish qualifications for a new society in case there’s assault etc, how do we work through it? How do we extend this to our prisons? This is what it becomes. This is what it needs to evolve to. And you need land to do this. This is why the encampments work.

So the encampments presented that beacon of light but how do we build beyond that? How do we get the adults? How do we get the disabled trans mother who’s working three jobs to feed her two kids to be a part of this? To feel secure in this world, this new society that is being built? This becomes the question. This becomes the vision.

Israel is but a mere instrument in the U.S.’s arsenal, an extension of empire. A 1492 narrative helps to situate what is going on in Palestine: We’re not just fighting the Israeli state, we’re fighting white supremacy and over 500 years of western colonialism and imperialism.

Indigenous sovereignty aren’t add-on units of analysis, so how is Land Back really being centered? How is Indigenous sovereignty and Black self-determination being centered in ways that actually contest and threaten settler sovereignty? There’s an ongoing genocide here on Turtle Island and we must contend with the monster in the mirror. Because this is how you stop the bleeding.

Gelender: When discussing movements, you often emphasize the distinction between “organization” and “mobilization” as Kwame Ture discussed. How is this distinction most relevant right now?

Abdou: Mobilization is when we move in this rhythm of endless causes instead of contending with the settler-colonial system as a whole. There is a tendency to go to actions as a means to acquiescence — a cathartic, self-indulgent action so you feel good about yourself and are able to sleep at night. Organizing means building alternatives and understanding the nature of the structures we’re contending against.

So the encampments are done and how do we evolve? How do we build the next thing? How do we take it to the neighborhoods? I said to the kids: Why aren’t we taking over neighborhoods? Why aren’t we buying buildings, establishing workers’ cooperatives? This is what the Panthers taught us.

This is the difference between organization and mobilization — in the encampment you took over land and you started to build. You made a temporary autonomous zone, in movement terms. But how do you do an urban Zapatismo kind of thing on a prolonged level? How do you build a social center? In Kingston we built a social center and it took us 10 years to build. Living quarters, music room, public library . . . and the same project in Oaxaca. This is the creation of alternatives, and it’s not easy.

How do you take the spirit of the encampment to the factories? To the neighborhoods? To cater to the people? Our martyr George Jackson said, “It follows that if a thing is not building, it is certainly decaying – that life is revolution and the world will die if we don’t read and act out its imperatives.”

If colonialism and imperialism stole anything, it’s our ability to dream dangerously. The Zapatistas have this wonderful saying and I will continue to say it as long as I have breath in me: “Holding each other’s hands, we ask each other what each of us knows and this is how we discover the revolutionary horizon together without leaving anyone behind.” This is what’s key.

LEARN MORE:

Follow both Dr. Mohamed Abdou and Amanda Gelender on Instagram.

Take the time to learn more about ‘Land Back’ and what it means, both in relation to Palestine and Turtle Island.

🔥🔥🔥🔥

Profound.